The Magazine of The University of Montana

Welcome to Dharavi

Art Project Sheds Light on Strong Community in Mumbai Slum

Story by Erika Fredrickson Photos by Casey Nolan

A local resident looks at the Artefacting Mumbai team’s Triangle Mural just after it was completed. The mural is on the main corridor where the team spent a vast majority of its time in Dharavi. cap2: Three migrant women sort plastics in a Dharavi recycling facility.

Photographer Casey Nolan says that no matter how many documentaries you watch, no matter how much you read, or how much you are briefed ahead of time, nothing truly prepares you for going to Dharavi.

The massive slum—one of the largest in Asia—is sandwiched between Mahim and Sion in the heart of Mumbai, India. It supports a million people on less than a square mile. Brick-and-tin shanties and crumbling apartment buildings are slung with a rainbow of laundry hung out to dry. The aroma of rich, spicy foods mixes with the stench of sewage and garbage.

“In India it’s sensory overload no matter where you go,” says Nolan, who got his undergraduate degree in 2002 from UM’s Environmental Studies Program. “There’s so much color and so many smells and languages. And Dharavi is the recycling district, so on top of the dense population it’s highly congested with trash and industrial pollution.”

In November 2010, Nolan set out with painter Alex White Mazzarella and photographer Arne de Knegt to document Dharavi with an art project they call Artefacting Mumbai. The idea was to explore an unexpected aspect of the slum: Despite its lot in life where 80 percent of the city’s garbage goes, it harbors a strong community.

It’s also in danger of extinction.

Dharavi is surrounded by Mumbai’s growing business center—and it is prime real estate. Investors want to bulldoze the slum and turn it into a mixed-use commercial and residential center. Artefacting Mumbai was a way to dig deeper into the culture of those whose livelihoods are on the line.

Three migrant women sort plastics in a Dharavi recycling facility.

Mazzarella and Nolan met in 2004 at Portland State University in Oregon, where they both were taking graduate courses in urban planning. While working on an urban planning project in Brooklyn, N.Y., Mazzarella—a visual artist—came across Dharavi. He was intrigued. He called up Nolan in Portland and proposed a four-month cultural exchange. The place would serve as inspiration for Mazzarella’s art, and Nolan could capture the behind-the-scenes, real lives of Dharavi residents. They recruited de Knegt, a photographer from Holland, and spent all of 2010 fundraising. In November they gathered their gear and set off for Mumbai.

“We went there with this idea of almost being like anthropologists, but using art to document the strength of the community—its social wealth,” Nolan says.

“We didn’t understand the reality of Dharavi until we got there.”

Earning trust

The ACORN office and community center, where the team set up a studio and held art classes, was the site of the first public mural.

It was in Dharavi that the 2008 Academy Award-winning film Slumdog Millionaire was shot. The movie, about a boy from the Dharavi streets who ends up on the Indian version of the television game show Who Wants to Be a Millionaire, garnered critical praise. But the truth is, in the wake of the fairytale hype that surrounded Slumdog Millionaire, the real Dharavi was forgotten.

“There is a lot of resentment in the neighborhood about how that was handled,” says Nolan. “It was people coming in with cameras, producing things, and then leaving and really never being heard from again. We didn’t want to set that same tone.”

The first few weeks the artists rarely used their cameras. Walking through the neighborhoods, they often were met with skeptical looks. Nolan recalls one businessman asking them point blank why they were there. After all, people don’t vacation in Dharavi; if you go at all, you take a picture and leave quickly.

“And it’s not just Westerners,” says Nolan. “A lot of people who were born and raised in Mumbai have never been to the slum because they were either fearful of it or they saw no reason to go.”

Nolan describes the first week as “relatively uncomfortable.” The extreme poverty was difficult to witness. And Nolan says he initially mistook Dharavi for a dangerous place.

Sorab is one of the chicken butchers in Dharavi’s Thirteenth Compound who captured the team’s attention with his beaming smile. “He radiated a joy for life that transcended his gruesome job at a gloomy work space,” Nolan says.

“I was constantly making sure I had my wallet,” he says. “I was watching my camera extra carefully, and my backpack with my electronic equipment was always close and tight to my body.”

Language was a barrier even with interpreters. The artists’ original intent to do an in-depth analysis of the Dharavi community was proving difficult. But there was hope. One thing they had going for them was their art. The trio taught art classes to children at a community center donated by the ACORN Foundation of India—a Mumbai nonprofit that advocates for the people of the recycling district by fostering a sense of community and giving them a voice. They also created public sculptures and murals. “People would stop and stare,” says Nolan. “We were very novel—like a circus show. We decided we could embrace that and do more public art.”

Within a few weeks, some people in Dharavi started warming to the strangers. Ashish, an eighteen-year-old who took art classes, inspired the artists with his energy. A ham in front of the camera, Ashish would dance and make a heart shape out of his hands, put it in front of his chest and move his fingers up and down so that the heart would beat.

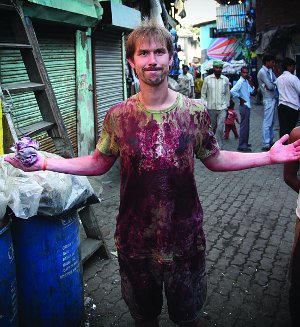

Casey Nolan is covered in wax after helping facilitate an art experience with the Dharavi kids. Photo by Arne de Knegt

Ashish’s gesture ended up being a colorful image they painted as a mural on the community center.

The artists also were inspired by the local chicken butcher, Sorab, whose shop they passed on a daily basis.

“The shop almost looks like something out of a horror movie when you’re just observing it,” says Nolan. “There’s a lot of metal and wood and blood spatters. But Sorab has this most contagious smile. Every time we’d walk by he’d have this ear-to-ear grin with these bright white teeth smiling at us and these big, oversized, inviting eyes.”

Mazzarella made paintings based on Sorab, and Nolan took photographs of him.

“He became an icon for the joy of life that we found there,” says Nolan.

The artists were still constantly being watched, but more and more in a positive way. Every night they’d head back to their apartment just across the railroad tracks to catalog photographs, post on their blog, and regroup. About two months in, Nolan noticed a change in himself. He no longer worried about danger. Instead, he settled in, eating at his favorite restaurants and stopping in for tea with new friends. “It’s such a nonaggressive society,” he says. “I never felt threatened. I never felt concerned for my or my project partners’ personal well-being. I remember walking around thinking that this is my community right now. For all three of us, Dharavi became home.”

Families that live along the Tulsi Pipes, which are municipal water pipes, consist primarily of people in Dharavi’s recycling industry.

The exhibit

All the discussion about recycling, consumerism, and globalization that Nolan engaged in during his years in UM’s Environmental Studies Program took on a whole new dimension in Dharavi. He watched people sorting through plastic, cleaning it, and making it into pellets, and then selling it back to toy and toothbrush companies for a cheap price. It provided jobs for people with few options, but the conditions were far from ideal.

“I struggled with it,” he says. “I was seeing the full circle of what’s necessary to make a consumer lifestyle possible.”

Because it’s a recycling district, all kinds of curious discarded objects end up there. One day the artists attended an exhibit outside of Dharavi by famous Indian artist Anish Kapoor. In the exhibit, red wax was shot from a cannon onto a giant white wall. The canisters that housed the wax ended up in a recycling warehouse in Dharavi a few days later. The artists happened to stumble upon them and recognized them immediately from the exhibit. They couldn’t believe it.

“It was obvious there was a story there,” says Nolan. “These pieces that came from the most influential artist in India in one sector of society ended up in this sector of society that is mostly ignored, with the people that clean up the waste of everyone else.”

Nolan works on building the Bottle House installation for an exhibition in Dharavi. Photo by Arne de Knegt

The artists bought forty of the canisters from the recycling warehouse. With permission from Kapoor’s manager, they took kids from Dharavi to Kapoor’s art show so they, too, could witness the cannon shoot red wax. Later Nolan and the others met with Kapoor, who donated materials from his exhibit to the Dharavi kids to recycle back into their own art pieces.

“The kids got to see the exhibit and then they got to do their own expression of it with the red wax by throwing it against a white wall,” says Nolan.

During the final month of their stay, Nolan, Mazzarella, and de Knegt put together an exhibit—a culmination of all the video footage, photos, paintings, and sculptures they’d created. The art was mostly produced by the three artists, but people in Dharavi who had become friends of the trio and muses for their work facilitated the exhibit.

It was a walking gallery that took place in sixteen spaces around Dharavi, including at people’s homes and businesses. Hundreds of people from outside Dharavi made their way into the slum where, among the rust and metal of the industrial area, they were greeted with a welcome mural. Down a serpentine road, several workshops and warehouses displayed photo exhibits and film projections the artists had created, inspired by Dharavi. A three-story building hosted paintings and experimental films.

A young boy entertains his grandmother with a recycled drum.

With Kapoor’s canisters the artists built a six-foot-tall and six-foot-diameter walk-in structure, which they called Beehive. Nolan had created a soundtrack that visitors could listen to inside the hive. It was the sound of bees buzzing combined with the sounds of Dharavi: metal splitting, pounding, plastic being ground down. People talking. A man singing.

“We recorded people’s reactions that day,” says Nolan. “So many people were really stunned at what they saw. They expected it to be a scary, uncomfortable place. Instead, they saw the friendliness and the humanity and the joy for life that exists there.”

Some locals brought out their own art pieces to show, and one man made newspaper hats for the children. Many Dharavi people continued their work of recycling throughout the day, but they also stopped to watch the spectacle as people who had never set foot in the slum explored the streets.

“It could have been almost artificial but it felt organic,” says Mazzarella. “People from all over Mumbai went into this slum in the name of an art exhibition. But, in the end, what really happened is they saw the reality of people here. And what they saw broke down their preconceived notions of the slum. For a day it made the gap a little bit smaller.”

Dharavi resident Laxmi, left, her daughter Sheetal, and a neighbor sit inside the Beehive installation. Beehive was built entirely from recycled materials found in Dharavi and featured an audio track of bees buzzing mixed with recorded industrial sounds of items being recycled.

The aftermath

In July 2011, less than six months after the artists departed Dharavi, a small section of slum was leveled. Warnings of more bulldozing have been issued. Nolan says the media haven’t been allowed into the slum, and, with little technology to communicate, the artists haven’t been able to reach their friends who live there.

“It’s still really hard to say whether this is the start of a larger demolition or not,” says Nolan.

If it’s demolished, the two other canister beehives, which were built on rooftops, and four murals will most likely be destroyed along with Dharavi’s hard-built homes and businesses.

For now at least, the slum’s future hangs in the balance. Meanwhile, Nolan and the others continue to advocate for Dharavi through art. The Dharavi exhibit is now booked for galleries in Boston, New York City, and Portland, Ore. Mazzarella and de Knegt have tentative plans to go back to Dharavi to look at opening an official art center for children. Mazzarella recently returned from Europe, where he led shorter Artefacting workshops for marginalized communities in Rome and Oslo, Norway. A six-week project in Detroit is planned for this fall.

But nothing will be quite like Dharavi.

“These people are doing jobs that none of us want to do,” says Nolan. “Those are the cards they’ve been dealt, and they make the most out of it. With very little they find a lot of happiness in their lives. That alone was one of the most powerful lessons.”

For more information on the project, go to www.artefacting.com.

Erika Fredrickson is the arts editor at the Missoula Independent. She graduated from UM’s Creative Writing Program in 1999 and received a master’s degree in environmental studies in 2009.

Email Article

Email Article